Formation of a Revolutionary

Seamus Ruddy was born and baptised as James Kenneth Ruddy in the Ballybot area of Newry, County Down on the 2nd June 1952. He was the 8th of a family of 9 and the youngest male born to mother Molly and father John.

His birth name and town were strong indicators of his place and future prospects. As a Catholic born in a nationalist town the English birth certificate version of his name reflected the Northern Ireland state’s proviso on having births registered with Gaelic names.

The Newry that Seamus was born into was then a town of 24,600 people and few economic prospects. As the southern most town of the Northern Ireland statelet its natural economic and political hinterland was cut by the border with the Republic of Ireland. Newry’s dominant activity of the 20th century was largely the export of its population. Between 1926 and 1951 Newry’s population fell from 26,336 to 24,609 losing large natural increases to three corners of the world: the Americas, the UK and Australia.

Newry was a poor town and Ballybot one of the poorest parts of it. Newry historian Tony Canavan (in Frontier Town) recounts:

"The district of Ballybot on the far side of the Newry River was settled by people from the neighbouring countryside as the town grew because there was little or no room in the old town. Initially, the people who established themselves in Ballybot were poor people who had come to Newry seeking employment as labourers, dockers and servants and this gave rise to the name An Baile Bocht 'the poor townland' ".

However, the Ruddy household benefited from a father who was a butcher. In the general poverty of Newry and particular poverties of Ballybot they would have appeared as one of the more stable and ‘better of’ families. As a regular earner John Ruddy was one of a relatively lucky few who were able to readily get a council house in the Ballybot area.

Newry suffered greatly from a lack of decent housing stock and it was a major political issue in the 1950s, and an important factor in the elections to Newry Urban District Council in that period. Newry Urban District Council became very active in building council houses in the mid 1950s and local old fashioned nationalist politics had to yield to a new brand of more radicalised labour movement based politics.

Newry Urban District Council was one of a few in the Northern Ireland statelet that was not Unionist-controlled. The Newry branch of the Irish Labour Party had emerged from the split with the Northern Ireland Labour Party that had taken place in 1948-49, essentially on the question of partition and the legitimacy of the Northern Ireland statelet. Local Newry labourite and political maverick Tommy Markey was part of the group that swept out the old nationalists from control of the council in 1958.

An occasionally abrasive character Markey himself was to fall foul of the national question when he took the salute of a British Army recruiting regiment in 1967 which crystallised long-standing disagreements within the local Newry Branch of the Irish Labour Party into a series of splits, and led to the formation of the Newry Labour Party. Markey was a Ballybot man and had a strong enough local following to weather the electoral storm. In the period [date] Newry Labour Club on Patrick Street was also founded which was an important factor in the Ruddy family (father John was a leading member).

The changes in Newry and Ballybot were evident across the 1960s with new council houses bearing the names of Irish labour heroes who were executed after the 1916 Easter Uprising: old persons’ dwellings at James Connolly Park and council houses in Michael Mallin Park. Seamus and his family lived in Michael Mallin Park.

The tension between nationalist and labour politics was a constant theme in Newry politics, particularly from the 1960s onwards and was both a key influence and point of departure for Seamus.

In the 1950s the town was briefly touched by Operation Harvest the Irish Republican Army’s (IRA) Border Campaign that lasted from 1956 to 1962. Initiated by the northern command of the IRA it marked the rebirth and rejuvenation of militant republican action and politics. Operation Harvest was not a military success. However, it was politically very successful gaining sympathy and support across Ireland North and South, with Sinn Fein and anti-partition candidates achieving electoral success. It was a further blow for the old styled nationalist politicians in Northern Ireland’s nationalist communities.

Although largely focused on the rural areas and the border Operation Harvest left few marks on the town but did provide some lasting vestigial political linkages which would touch Seamus’ and other’s lives in the late 1960s.

One of the linkages was the memory and commemoration of the Edentubber tragedy. On the 11 November 1957 five young IRA activists died in an explosion at the foot of Edentubber Mountain in County Louth, a few miles from Newry. One of the young men was 19 year old Oliver Craven from Ballybot, in Newry. Another was 19 year old Smith from Bessbrook.

The psychological marks of the IRA border campaign were probably more marked. Against the backdrop of rising unemployment and mass emigration in the 1950s it underlined a new readiness in the nationalist communities neither to accept, nor to remain quiet in the bad times.

In the 1960s the international economies, the United Kingdom (UK) and Irish economies (North and South) were throwing off the legacies of post World War II austerity and experiencing a long boom. For the UK the 1960s was a period of unprecedented growth and prosperity, of full employment.

Although ostensibly part of the United Kingdom Newry and most of the nationalist areas in the Northern Ireland statelet were peripheral to this boom and unemployment levels in this period continued to exceed 10%. Manufacturing jobs actually declined in Newry; from 3,348 in 1959, to 3,260 in 1971 and 3,211 by 1978. Newry and Strabane both frontier towns had exceptionally high levels of unemployment throughout the 1960s. By 1970 Newry had the second highest unemployment rate (13.9% against Strabane’s 16.9%). This underlined the gap between Newry and the rest of the ‘booming 60s’.

In the 1960s the Unionist government of Northern Ireland was focusing policy, resources and development on its supporters’ heartland; the founding of the new town of Craigavon near Portadown and siting of a new university at Coleraine rather than Derry.

Poor infrastructure and the 1964 cuts of the railway branch line to Newry had left Newry even more isolated. There was little industry in the area and the quality of what was attracted was poor and quickly gained a reputation as ‘fly-by-night’; taking grant aid and closing soon after. Seamus’ awareness of these problems and issues was a household matter; his brothers, notably Terry were campaigning for jobs and industry and against Seenozip fly-by-night operations. Indeed, Seamie’s brother Terry was a victim of the 1964 scandalous closure of Seenozip when two its directors absconded with the company’s and £30,000 of government money. (They were subsequently caught, tried and jailed. It also brought an end to Unionist MP Patricia McLaughlin’s career. She had been instrumental in bringing the firm to Newry in 1960 and had been a director of the company from its 1960 until 1962. In 1964 she resigned for health reasons.)

Newry’s distance from the Northern Ireland state’s public “goods” and closeness to social and economic “bads” became exacerbated in the 1960s. As the post war ‘baby boom’ came of age in Newry it added a new urgency and impetus for change. As part of the tail end of the baby boom Seamus was to find himself swept up and at the vanguard of the emerging opposition to the failures of the Northern Ireland state to deliver the most basic of rights and amenities for nationalist communities in towns like Newry.

Growing up in the 1950s and early 1960s Seamus saw all the tensions and problems on his doorstep. An overwhelming police presence during the IRA Borders campaign was a commonplace of Newry life as was the steady stream of departing relatives and neighbours to work elsewhere. However, Seamus’ days in Michael Mallin Park and Ballybot were carefree and largely idyllic; everyone was poor, nearly everyone was Catholic and nationalist, everyone got by in a fashion. This was the state of things that Seamie grew up in and to inherit.

Ballybot Days

Seamus’ bright and sharp mind alloyed with a sharp sense of humour found him a ready network of friends. Although not a great sportsman at the school staples of Gaelic football or hurling, or in the lively Ballybot soccer league he was a popular figure and always in the thick of the crowd.

He was able to achieve academic success in his easy going way. Whilst fond of books he had little time for homework; at least not his own. He was never seen doing his own homework, but would readily help everyone else with their homework. With his natural intelligence and sharp wit did not grate as he helped; he never made people feel stupid. A born teacher in the real meaning he helped draw talent from friends and family.

In 1963 Seamus passed the 11-plus selection test for secondary school streaming and he found himself heading to the Christian Brothers at the Abbey Grammar School across town. By 1966 problems with his eyesight forced him to wear glasses, with his nieces and nephews seeing the academic look took to calling him “The Professor”.

The Christian Brothers of the Abbey Grammar School had a reputation for enforcing discipline through rigorous corporal punishment. This was vigorously and roughly delivered to anyone who stepped out of line. Seamus often found himself the brunt of this and his rebellious nature and sense of fairness and justice rankled with the atmosphere of the muscular enforcement of control at the Abbey. In 1970 Seamus readily left for the newly built Newry Technical College on Patrick Street to do an Ordinary National Diploma in Quantity Surveying.

Newry Technical College had many attractions: it was on his door step (250 metres away), was co-educational, had an adult atmosphere (and no uniform or control of hair length), and many of his friends were going there too. The relaxed atmosphere of the Tech as it was called was evident at lunchtime where the school supplied a record player for the students’ common room. Seamie and

his friends were into rock and the blues and lunchtime became a feast of the cutting edge of hard rock music. A fan of John Peel Seamie’s tastes extended from Jimi Hendrix, The Groundhogs, The Taste, Tir na Og, Horslips and the Chieftains. Long-haired and moustached Seamie and his friends were the epitome of advanced cool, part of Newry’s own small manifestation of the “hippy” age.

The commemoration of the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising saw an outpouring of pride and restless in nationalist areas in the north of Ireland. The RTE had an excellent dramatisation of the 1916 uprising which Newry people avidly followed. There was also the Biafran war in 1967 in Nigeria where the predominantly Catholic secessionists were ruthlessly suppressed by a state armed and supported by a British Labour government. Newry’s first black residents were refugees from the war and terrible famine in Biafra.

The openness to culture and music beyond Newry was also evident in the ideas that Seamie and other young people in the town came into contact with. The American Black Civil Rights movement and anti-colonialist struggles in the Third World became a reference point and source for ideas on local action.

In the 1966 a local ex-school teacher McGuigan opened a new bookshop on Monaghan Street (it soon moved to Lower Water Street) and its bright stock of new Penguin paperbacks as well as those of Irish publishers (Anvil, Mercier, Gill & McMillan) fed hungry minds with new facts and ideologies. Seamie like many other hungry young intellects was a customer.

Newry’s baby boom generation benefited from the British 1944 Education Act, which instigated free universal secondary education (and subsequent extensions of this principle to include higher education) and they went to university as never before. The citadels of knowledge until the 1960s had seen as the birthright of the only the upper middle classes or the occasional scholarship kid appeared overnight as more democratically accessible. Young minds went to be filled with new ideas and when they came back they brought these and the books they read home. Their copies of left books and influences came into circulation amongst Newry’s young people. Seamie’s coming of age in Newry was at a period of fundamental political and social change and he was to become one of the generation who sought to change that in an anti-colonialist direction.

1968-1969

The relative failure of old-fashioned nationalist politics and of the IRA’s border campaign in the 1950s was all too clear to a younger generation coming of age in the universities of the late 1960s. In the 1960s in the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) was founded on 29 January 1967 at a public meeting in the International Hotel, Belfast. Initially attended by all political parties in Northern Ireland the Ulster Unionist Party quit the meeting. NICRA had a reformist, non- party and non-violent agenda: repeal of Special Powers Act (which provided powers of internment without trial), one-man-one-vote, an end to gerrymandering, disbandment of the B Specials paramilitary police force, an end to discrimination in the awarding of local authority housing, and an end to discrimination in government employment.

NICRA organised a march Derry on 5 October 1968 which was subsequently banned. The civil rights marchers defied the ban and were met with baton-charges from the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC). Many marchers, including West Belfast MP Gerry Fitt were injured and television pictures of the savage suppression of the march shocked viewers across the world. Two days of rioting in nationalist areas of Derry followed. NICRA were appalled but were prevailed on to suspend all marches less clashes and violence arise.

However, there were those in and around NICRA radicalised and this gave impetus to the founding of more radical groups, notably People’s Democracy (PD) on the 9th October 1968 at Queen's University Belfast.

Stirred by the events in France May 1968 Michael Farrell said that PD’s “formation was considerably influenced by the Sorbonne Assembly and by concepts of libertarianism as well as socialism. It has adopted a very democratic type of structure; there is no formal membership and all meetings are open.” (New Left Review, June 1969, Issue 55)

The People's Democracy rejected the government's ban on Civil Rights marches. In imitation of Martin Luther King's Selma to Montgomery marches, PD held a march between Belfast and Derry starting on 1st January 1969. The march was repeatedly attacked by loyalists (including off-duty members of the Ulster Special Constabulary) along its route. There was a particularly bloody and violent ambush at Burntollet Bridge on Saturday the 4th January, when the marchers were attacked by about two hundred loyalists armed with iron bars, bottles and stones. Notoriously the RUC stood by and allowed the march to be attacked.

The next day in the early hours of the morning of Sunday 5th January 1969 the RUC ran amok in St Columb's Street, Derry smashing every window on the street and threatening and rough handling men and women trying to stop them.

The Nationalist communities across the North felt as if they were under siege from the Unionist state and its organs of “law and order”. The latter displayed little or no restraint in the way of law and order. The overwhelming mood was of fear, especially amongst adults who could recall histories of pogroms and repression. But there was also a strong and growing undercurrent of defiance and a will to change the rotten society were voting, housing and access to employment had been so long denied to nationalist communities.

Newry January 1969

Thus tensions were very high in Newry on 11th January 1969 when the scheduled PD march was to take place. The march had been organised by Newry PD, a group set up by local civil rights supporters. It was a much more conservative group composed of older and more professional figures than PD elsewhere; its roots and social composition was not at all like the students and young activists that typified PD in Belfast. However, this more ‘middle class’ and professional profile did not prevent the march from being banned from entering Sugar Island, a supposedly Unionist part of the town. This ban came although the mainly Protestant owned businesses in that area disagreed with and opposed the banning of the march.

Setting off from Edwards Street Car Park on a very cold and foggy Saturday the 5,000 strong march was stopped at the Savoy Cinema at the junction of Monaghan Street and Merchants Quay by RUC barricades and a phalanx of police in full riot kit. The RUC barricades were on Merchants Quay so most of the marchers did not see this and continued to funnel forward towards the barriers. The march organisers tried to negotiate passage past the barriers but the RUC senior officer adamantly refused. Tempers flared as the marchers pressed against the barriers, with pushing and counter-pushing, as batons and riot shields were drawn and used. (A group of Paisley-ite counter demonstrators led by Ian Paisley and Major Bunting were behind the police barricade.)

The stewards were unable to contain the numbers of people or their emotions which were mainly vented on the tenders that blocked the marchers’ route. One of the tenders was pushed into the canal and another set on fire as darkness fell.

Seamie was present on the March and the subsequent meeting of PD members in the Annex of Newry Town Hall. The latter was a hot and unstructured exchange about tactics and strategy with particularly fierce personal clashes between Bernadette Devlin and a small but vociferous group from Armagh. The long political debates achieved one agreement: to occupy Newry Post Office. Seamie did not join them in the Post Office occupation but he had more or less thrown cast his lot with PD.

Newry PD of 1969 after the January march became more like PD elsewhere: a heterogeneous political mix of restless individuals and intellects ranging across social democratic, anarchist, socialist, Marxist and Trotskyite tendencies. It met where it could; for example, in St Colman’s Hall, and at the home of the Damian Boyle (brother of Kevin). As the troubles escalated PD’s power as a broad-based mass movement dissipated and it began to move increasingly to resemble a more new-left type party.

Thus the Newry branch of PD evolved into a small and influential group that navigated its way through the splits and tensions between Official Sinn Fein and Provisional Sinn Fein. This was a period of political controversy as well as tremendous activity. The new party’s paper: The Free Citizen was there to be distributed and sold; its ideas to be given a wider platform. The influence and prominence of socialist and revolutionary politics became more pronounced in PD’s politics and paper.

Marches on unemployment and jobs helped to give Newry PD and Seamie more profile, experience as well as confidence. Never far short of the latter Seamie threw himself into the debates, paper selling and marches with typical energy and humour. In that period Newry PD produced a local supplement which was cyclostated and was mainly marked by humour and comment rather than theoretical discussions. Seamie largely organised, wrote and produced this from the front parlour of Malin Park, or in the house in Nicholas Court that was to become the base for PD meetings and other adventures in the 1970s.

Certainly there was not much to be happy about in Northern Ireland or Newry. Unemployment was still high, civil rights were still denied and the RUC continued its violent and unbridled suppression of nationalist dissent.

A State of Repression

The fear in the Nationalist ghetto was being transformed into fierce resistance with the RUC being met with stones and petrol bombs. The fate of the Nationalists in Derry became a focus point of all of North and the world’s attentions as the RUC were met with riots.

In April, the RUC made a fatal and fateful attack on nationalists in Derry. A local man, Samuel Devenny, was badly beaten by RUC members who broke into his home after a riot in the Bogside on 19 April 1969. The RUC also batoned Samuel Devenny’s teenage daughters in the attack, which became a byword for the violence and brutality of the police. Samuel Devenny died from his injuries on 17 July the first victim of The Troubles.

Rioting continued throughout the months that followed with the marching seasons of July and August culminating in some of the fiercest resistance yet to the RUC entering the Bogside, in Derry. In August “Derry’s Young Hooligans” held the RUC at bay despite the wholesale mobilising of its ranks into what became known as the “Battle of the Bogside”. The growing fear that there might be a violent catastrophe in Derry gripped the whole island with Jack Lynch, the Irish Prime Minister mobilising the Irish Army and sending it to the Border. His speech said that he “would not stand idly by” and the crisis escalated. Riots broke out in Belfast as nationalist tried to help take pressure of besieged Bogsiders. In Belfast Loyalists burned out many Nationalist homes with whole streets being burnt out.

The widespread international outrage at the indiscriminate violence of the RUC saw the British government begin to take closer and more direct control of the “security situation” in the North.

In August 1969 the British government’s response to the growing concerns about Northern Ireland and its governance was to send in British troops. The appearance of troops in nationalist areas provoked many concerns. Certainly there were some that had some sense of relief at their deployment on the basis that there might be some respite from the RUC’s violence and repressive actions. The so-called honeymoon had begun. It did not last long.

Developments within the republican movement were also moving on. Sinn Fein’s Ard Fheis in January 1970 had revealed strong differences in the movement and there was a walkout on a question of a continued focus on traditional ‘physical force’ approach as opposed to greater emphasis on electoral politics. This was felt in areas such as Newry with growing tensions within the republican movement as the more traditional republicans emphasised the need for action against the “Brits”. There was strong ideological current to the emerging split with the traditional taking a more centrist and less politically radical stance and the ‘official’ Sinn Fein movement moving more leftward and away from the physical force tradition.

In the emerging crisis Seamie’s politics remained resolutely in the PD camp although there was continuing ideological evolution as well as personal and political strains within the broad left movement that was PD in 1970. Seamie honed his ideas through wide-ranging reading taking in the works of James Connolly, Marx, Lenin and the new revolutionary leaders in the emerging world particularly Latin America. He wore a James Connolly badge.

A Date with the State: The 1970 Irish cement strike

PD’s journey leftward saw it embrace workers’ cause across Ireland as well as in foreign lands. Anti-colonialist struggles in Africa, particularly in the Portuguese colonies and the plight of the Palestinians became causes close to the hearts and minds of PD activists. Writers such as Che Guevara, Regis Debray, Amilcar Cabral, Frantz Fanon, and Fawaz Turki and James Connolly were sources and influences, especially the latter as there was a very active movement by a series of publishers and political parties to reprint Connolly’s works.

There were also more local practical fall outs of class politics and solidarity. In 1970 supporting the Drogheda cement workers’ strike became a high priority as the dispute dragged on and especially as a new generation of gombeen men sought to undermine the strikers and make easy money by shipping in boatloads of cement to desperate contractors. The ports of the North of Ireland became a major axis for this ‘scab cement’.

Dubious characters gravitated to lucratively supplying cement at high prices to building firms scabs were running cement imports via small ports such as Newry and Ardglass. Demand for cement was high and these callous gombeen men, often small time crooks and fixers were making a fortune. It was a bitter dispute with scab cement runners guarding their lorries with shotguns. Strike supporters responded by clandestinely setting fire to trailers of cement when they could. Unionised firemen helpfully added thousands of gallons of water to these trailers when they were called to the blazes.

John Rocks of Armagh organised a mini-bus to take PD members to Ardglass to picket and block boats from unloading cement to break the strike. On the mini-bus from Newry were Mickey McCullough, Seamie Ruddy, Christopher Ruddy (no relative), and Leo O’Neill. Leo O’Neill, a photographer with a studio on John Mitchell’s Place was the ‘official’ photographer of Newry PD and his duty that day was to film events as they unrolled. His duties and position slightly separated him from the events and meant that he was only one of the bus passengers not to be arrested for ‘riotous behaviour’.

There was a degree of trepidation amongst those that went to Ardglass as the RUC Special Patrol Group would be there and the Group had a reputation for dealing out rough treatment to protestors. The RUC Special Patrol Group were young, thuggish and saw nationalists, and more particularly ‘lefties’ and ‘commies’ as fair game. Their poor reputation preceded them and they regularly featured on the pages of the Free Citizen, the PD’s newspaper.

The port of Ardglass is small, with little room for tactical manoeuvre and the RUC had all the advantages and mass arrests of the protestors followed. Mickey McCullough and Seamie Ruddy were convicted of riotous behaviour and sentenced to 6 months suspended. Mickey McCullough was stressed with the situation and felt that PD had done very little for him. His then girlfriend was the daughter of a leading figure in Official Sinn Fein - the Workers Party and Mickey drifted off from the PD to the “Officials”.

Seamie took this brush with the state in his stride and made light of the possibility of having to study for his “A” levels whilst ‘inside’. Mickey McCullough was less sanguine. Of a more nervous disposition Mickey was reasonably and rightly worried that the state might make an example of the PD protestors and particularly as there was already a blanket rule that riotous behaviour automatically garnered a 6 or 12 month jail sentence. Although Seamie was worried by the prospect of 6 months imprisonment he did not want to show it and treated the prospect in a bluff, offhand manner.

This was Seamie’s first official brush with the state (and the prospect of prison) had finished in stalemate. It did not cramp Seamie’s political interests or opposition to the state. If anything the events imbued his natural confidence and strengthened his belief in his ability to survive hardship.

As Mickey McCullough drifted off Seamie became more involved in local PD and the politics of opposition and action against the Northern Ireland state and its institutions.

Newry in the 1970s

The Newry of the 1970s seemed like a town under siege from the state and with little prospects for economic growth or peace. Across the early 1970s a series of deaths underlined the intensity of the crisis and that it had moved into another very dangerous phase. There was no escaping the ruthless confrontation of the state and the consequences of struggle were all too often tragic.

23 October 1971 - Sean Ruddy (28), James McLaughlin (26) and Robert Anderson (26) were shot in a premeditated, pre-planned shoot-to-kill operation by the British Army who secreted themselves on the roof of Woolworth’s overlooking the bank in Hill Street. The British Army claimed to have a tip off that the bank was to be bombed. The dead men were not armed, nor did they possess explosives.

On the 22 August 1972 - Oliver Rowntree (22), Noel Madden (18) and Patrick Hughes (35), all members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army and Francis Quinn (28), Patrick Murphy (45), Michael Gilleece (32), Joseph Fegan (28) and John McCann (60), all Catholic civilians, and Craig Lawrence (33), a Protestant civilian, were all killed in a premature bomb explosion at the Customs Office, Newry.

24 December 1973 - Edward Grant (18) and Brendan Quinn (17), both Catholic members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and Aubrey Harshaw (18), a Protestant civilian, were killed in a premature bomb explosion at Clarke's Bar, Monaghan Street, Newry.

15 May 1974 - Colman Rowntree (24) and Martin McAlinden (23), both members of the Official Irish Republican Army, were shot dead by the British Army shortly after being captured while preparing a land mine in Ballyholland, near Newry.

“The duty of a revolutionary is to make revolution.” – Regis Debray

In the early 1970s PD’s theoretical, political and organisational evolution continued a pace. The original heterodoxy and openness gave way to tighter branch structures with a Central Committee composed of branch delegates and the principles of democratic centralism. There was also a strengthening and broadening of intellectual and solidaristic links within the old left but also particularly the ‘new left’.

The latter had dated back to April 1969 when the New Left Review had interviewed amongst others: Bernadette Devlin, Michael Farrell, Eamonn McCann, and Cyril Toman (mis-spelt Taman in the NLR introduction). PD gained Tariq Ali’s blessing that the organisation was a true inheritor of the revolutionary legacy of Paris 1968. The ‘old left’ in the form of the Fourth International was also courted with their theoretical journal Imprecor devoting considerable space to the Irish crisis and broadly supporting PD’s stance.

PD also established links with international groups such as Italy’s Lotta Continua but also, on an informal basis, Palestinian groups including Palestinian Front for the Liberation of Palestine and the Popular Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine.

(To be continued) Mickey

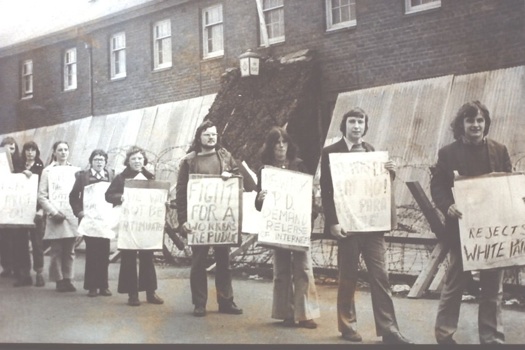

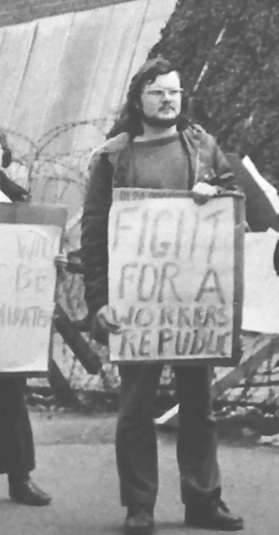

Outside Edward Street Barracks, Newry.

Photo courtesy of Gaeláras Mhic Ardghail